HOUSE HISTORY

An important aspect of any village history site is the investigation and documentation of the village's vernacular architecture. This is often referred to in short as "house history work", and it involves the study of all available documentary records for a particular property and its successive owners, plus careful study of the form and construction of the property and its associated outbuildings where relevant.

In Crick, a conscious decision was taken to carry out a large-scale house history project for as many as possible of the village's historic buildings within the scope of a formal project, which is referred to as the 'Crick Historic Building Record'.

The Crick Historic Building Record

The aim of this project is to investigate and document the history of Crick's older houses, based on analysis of surviving property deeds, study of wills and other documentation about the people who lived in the houses – and of course, detailed examination of the properties themselves, both as they are today and via old maps and photographs.

Information in the deeds is checked and expanded via other documentation such as parish registers, Enclosure Awards, Land Tax returns, Land Surveys, census returns, wills etc., much of which can be found at the local county record office. This in turn permits educated guesswork about the dates at which changes were made to the fabric of the buildings – a large house partitioned to allow part to be let to lodgers, two adjacent houses knocked together to accommodate a growing family, an extension added, a barn converted into living space, some land sold off or acquired, and so on.

The Crick Historic Building project commenced in 2010, and it is expected that it will take many years to process and analyse the mass of detailed documentation that has been generously made available by the owners of many of Crick's oldest houses. In due course, a series of detailed house-histories will emerge from this analysis work, providing a unique insight into the development of the whole village over the last 2 or 3 centuries. In the meantime a "House History Recordl" document is available for every house or property so far examined.

Recent changes in English property law

The work to record and copy old deeds is especially important today, because recent changes in English property law have abolished the need for mortgage lenders to hold a copy of the property deeds as security for their loan – and further legal changes have meant that even the Land Registry does not now hold copies of old property deeds. The result of these legal changes is that, since about 2003, increasing numbers of solicitors, building societies and banks have been steadily destroying hundreds of thousands of old parchment and paper property deeds dating back to the 1800s, the 1700s, and in some cases back to the 1600s. It may seem incredible that such an enormous body of valuable historical material can have been casually earmarked for destruction in this way – but such is the case, and for many of our old village and town houses it is already too late to discover their history, for their deeds have been lost or destroyed.

Confidentiality

Any information that we receive from you will be treated in strict confidence. Information made available to us will not be divulged to any other party without your prior written approval. This particularly applies to:

Digital images of any deeds and associated documents made available to us (and in addition, we expressly do not record any recent property documents, or any sensitive financial or similar information).

Digital images of the interior of any property (and in addition, we expressly do not record any images that might endanger the security of the premises if made more generally available).

How to contact us

We are always willing to look at further documents, if the owners of a house are kind enough to let us see the early deeds to their property – just contact the Archivist by email in the first instance.

Capturing the Data

Many guides have been published to assist would-be house-historians. In practice, the historian can only use whatever evidence is available, however. So these web pages do not claim to be an authoritative version of How to Do It; it is merely a reflection of what information was available.

Basic Methodology

The method adopted involves three main stages of investigation

- Examining the deeds to the property

- Physical examination of the property

- Gathering data from other sources

Property deeds should first be photographed carefully, using a digital camera with at least 5Mpix resolution. If a separate file-folder is used for each property, and each of the photographs is given a meaningful filename commencing with the date-year of the document (eg: "1754 Crick, mortgage, A Jones to B Smith.jpg", etc), the images will automatically arrange themselves in date order, making it much easier to unravel the evolving story that is told by the documents.

The most useful documents tend to be Abstracts of Title, Conveyances, and Mortgages, because they generally include significant background facts about the owners and occupants.

Understanding the legal terms can sometimes be a challenge (for example, 'lease and release', 'common recovery', 'copyhold or customary tenancy', 'surrender and admission', the various different types of mortaging and arrangements for borrowing, and so on). A good legal reference book can be a great help in explaining such terms in plain English - for instance, "A Concise Law Dictionary" by P.G. Osborn. The Oxford English Dictionary is also a mine of useful information regarding archaic legal and other terms.

When the deeds have been transcribed and analysed, the results can usually be condensed for ease of understanding, into one or two summary sheets; another useful tool is the spreadsheet - especially when combined with family-history data culled from parish registers and other documents, see below under 'Supplementary data sources'.

Physical examination of the property

A physical examination should aim to establish the layout and dimensions of the main building, and any associated outbuildings. A walk around the property with the owner is generally the best method.

Keep an eye open for any special features that might give clues to dating, such as date plates, doorways/lintels, windows/fittings, chimneys (both regarding their form and their position within the house), staircases, ceiling and wall beams, roof timbers, specific period features (such as locks and bars, re-used timbers, decorative features etc), any signs of rebuilding (eg replacing cob with brick, timber framing with stone, raising the height of the roof, etc).

Take plenty of photographs, including close-ups of features of interest. But remember to obtain the owner's permission beforehand - and do not make any of this material public without specific permission from the owner.

Finally, old photographs, sketches, maps and paintings of the property can all be of great assistance in checking the previous history of the building - for instance, helping to establish dates for the blocking of a window or doorway, the addition or replacement of a feature, repair of a roof, etc.

Supplementary data sources

There are so many other potential sources of information that it is impossible to describe them all here in sufficient detail; a list will suffice to indicate the possibilities. Most of the documents can be found in the local county records office, and others (such as old newspaper reports) are now available via online database archives:

- Word of mouth reports

- Parish registers

- Census returns

- Wills and inventories

- Enclosure awards

- Militia List returns

- Hearth Tax returns

- Land Tax returns

- Newspaper reports

- Manorial records

Crick Village House Histories

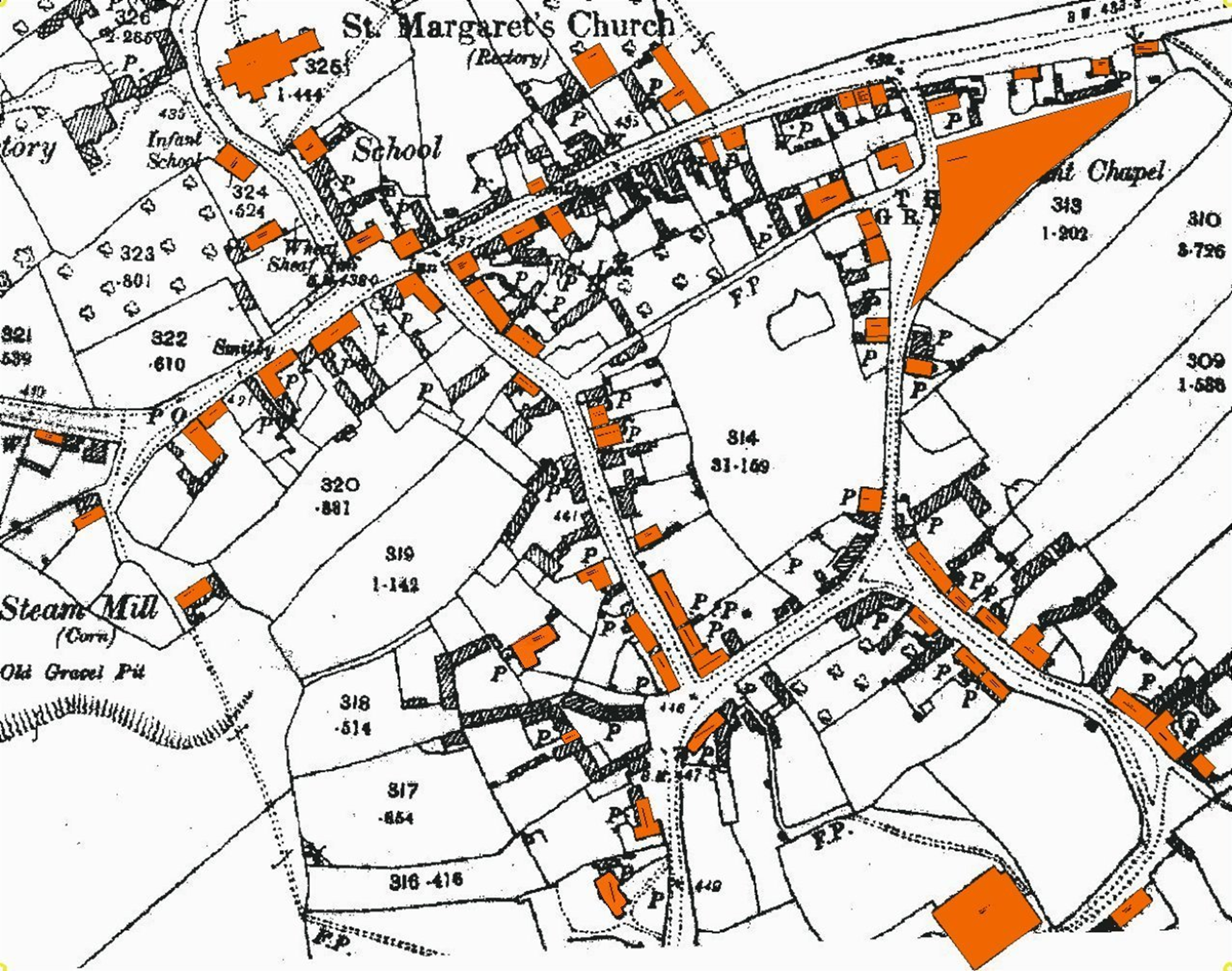

This map shows Crick in more detail. Six areas are highlighted, each leading to more detailed views of the respective areas.

A Medieval Water Meadows

Statements in Crick's manorial rolls throughout the Tudor period make regular mention of 'the great meadow' and 'the rush beds'.

Comparison of later documents (such as the Enclosure Award of 1778) and deeds for land and property dating from the 1800s, together with study of the modern Ordnance Survey map, show that the meadow in question was the low-lying stretch of land west of the village, where streams descending from the eastern and northen slopes come together. This area would have been subject to flooding in medieval times, and thus unsuitable for ploughland; however, it would not have been wasted, but used as valuable pasture in the early spring - an important resource for the village's flocks and herds.

The stream was not culverted, as it is today throughout the modern industrial estate, and its banks were lined in the 1500s with dense clumps of reeds. These reeds also had their use - they were a major source of fuel for the village bake-ovens (for Crick had no woodland at all, and timber was in such shortage in this lordship that the few trees that were growing were never used as fuel, but carefully saved for building material).

The manorial court rolls make regular mention of the reed-beds and the shortage of timber. For example, in 1536 Robert Kylworth was accused of having carried away rushes for fire-lighting, and was fined 12d (about one week's pay); and later in the same year we read that 'No-one may cut rushes except on his own land, on pain of a fine of 3s-4d. Bakers must put out their fires after they have withdrawn the bread, fine 12d.'

B Crick Village North

This map shows the north area of Crick in more detail. House HistoryRecords are available for:

- Church Street, No. 6, (Elms Farm)

- Church Street, No. 10(Cromwell Cottage)

- Church Street, No. 12

- Church Street, No. 14 (Meadow View)

- Church Street, No. 16

- Church Street, No. 19 (Churchside)

- Church Street, No. 31

- Church Street, No. 33 (Fennel Cottage)

- Church Street, No. 39 (The Hall)

- Drayson Lane, No. 5 (Pytchley Cottage)

- Oak Lane, No. 5 (Ash Tree House)

- Oak Lane, No. 12 (Oak Cottage)

- Oak Lane, No. 15 (The Poplars)

- Oak Lane, No. 17 (The Homestead)

- Yelvertoft Road, No. 24

- Yelvertoft Road, No. 26 (Ranmoor)

- Yelvertoft Road, No. 15 (Barley Croft)

The Church of St Margaret of Antioch dates back to at least Saxon times. In about 1077 AD the wooden built church, on the site of the preset Chancel, was replaced by a stone building. Over the centuries the church has been extended from its Norman structure with the addi tion of aisles and a spire.

The Doomsday Book (1086) records 32 households in the paish with a population of about 140 including a priest. Because of the numbers, Crick would have been considered a town. Most of the population would have lived beside or near the church.

Over the centuries the population spread out along the Oxford Way. This was the medieval route linking ecclesiastical centres of Oxford, Leicester and Peterborough. The Oxford Way roughly followed the line of High Street, Church Street and Yelvertoft Road.

Following the Black Death (1346 - 1352) many villages suffered from depleted population resulting property and land being laid to waste. This is believed to have happened in Crick and land was subsequently set aside for sheep grazing. The Welsh drovers would rest the sheep on pasture land before moving them on to East Anglia and then Europe. The drovers route through the village passed by what is now Lauds Road, Bury Dyke, Oak Lane and Drayson Lane. During the 16th to 18th centuries, farming and cottage industries of weaving, spinning and wool combing provided a livelihood for Crick people and buildings sprung up along the Oxford Way and drovers route.

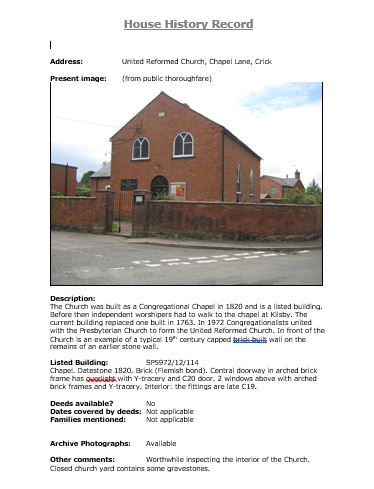

This map shows the central area of Crick. House HistoryRecords are available for:

This map shows the central area of Crick. House HistoryRecords are available for:- Boat Horse Lane, No.5

- Bucknills Lane, No. 1

- Chapel Lane, Nos. 6/7

- Church Street, Nos. 1-3 (the Manor)

- Church Street, the Old School

- High Street, No. 8 (Curfew House)

- High Street, No. 9 (Hill Farm)

- High Street, Nos. 16 &18

- High Street, No. 19 (Spencer House)

- High Street, No. 27 (Phoenix House)

- High Street, No. 31 (Hunters Gap)

- High Street, No. 33 (Owen Dicey's Shop)

- King Style Close, No. 1

- King Style Close, No. 2 (Cranbrook Cottage)

- King Style Close, No. 58

- Lauds Road, No. 7

- Lauds Road, No. 18 (Lilac Cottage)

- Lauds Road, No. 19 (Woolcomb Adams Farm)

- Lauds Road, No. 29 (Hghfields Farm)

- Lauds Road, No. 31-33 (Furlong House)

- Main Road, No. 15 (The Wheatsheaf)

- Main Road, No. 17, (Maltings)

- Main Road, No. 23

- Main Road, No. 28 (Well Cottage)

- Main Road, No. 37 (Home Close, aka Fairview)

- Main Road, No. 38 (Hillside)

- Main Road, No. 42 (Northgate House)

- Main Road, No. 56

- Main Road, No. 62 (The Retreat)

- Main Road, No. 76

- Main Road, No. 78

- Main Road, No, 80 (Woodbine Cottage)

- Main Road, No. 86 (Post Office, formerly Flying Horse)

- The Derry, No. 2

- The Derry, Mill House

- The Marsh, No. 1

- The Marsh, No. 2

- The Marsh, No. 4

- Watford Road, No. 6 (Vynter's Manor)

- Watford Road, No. 8, (Frant Lodge)

- Watford Road, land around former brickworks

- Watford Road, Hillcrest

- Watford Road, Mill Hill House

Statements in Crick's manorial rolls from the reign of Elizabeth the First mention that one of the village husbandmen named Ledger Banbury was leasing a close of land known as 'Brice's Close' in the 1550s.

Comparison of later documents (such as the Enclosure Award of 1778) and deeds for land and property dating from the 1800s, together with study of the modern Ordnance Survey map, show that this close was located alongside the road from Crick to West Haddon, which would have been a route for livestock being moved between pastures and market.

House HistoryRecords are available for:

- West Haddon Road, Home Farm